A few nice turning parts manufacturer images I found:

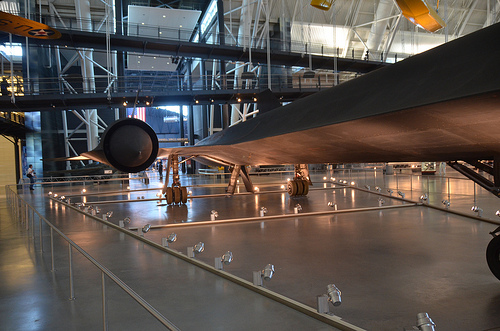

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center: SR-71 Blackbird (starboard profile)

Image by Chris Devers

See more photos of this, and the Wikipedia article.

Details, quoting from Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum | Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird:

No reconnaissance aircraft in history has operated globally in more hostile airspace or with such complete impunity than the SR-71, the world’s fastest jet-propelled aircraft. The Blackbird’s performance and operational achievements placed it at the pinnacle of aviation technology developments during the Cold War.

This Blackbird accrued about 2,800 hours of flight time during 24 years of active service with the U.S. Air Force. On its last flight, March 6, 1990, Lt. Col. Ed Yielding and Lt. Col. Joseph Vida set a speed record by flying from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in 1 hour, 4 minutes, and 20 seconds, averaging 3,418 kilometers (2,124 miles) per hour. At the flight’s conclusion, they landed at Washington-Dulles International Airport and turned the airplane over to the Smithsonian.

Transferred from the United States Air Force.

Manufacturer:

Lockheed Aircraft Corporation

Designer:

Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson

Date:

1964

Country of Origin:

United States of America

Dimensions:

Overall: 18ft 5 15/16in. x 55ft 7in. x 107ft 5in., 169998.5lb. (5.638m x 16.942m x 32.741m, 77110.8kg)

Other: 18ft 5 15/16in. x 107ft 5in. x 55ft 7in. (5.638m x 32.741m x 16.942m)

Materials:

Titanium

Physical Description:

Twin-engine, two-seat, supersonic strategic reconnaissance aircraft; airframe constructed largley of titanium and its alloys; vertical tail fins are constructed of a composite (laminated plastic-type material) to reduce radar cross-section; Pratt and Whitney J58 (JT11D-20B) turbojet engines feature large inlet shock cones.

Long Description:

No reconnaissance aircraft in history has operated in more hostile airspace or with such complete impunity than the SR-71 Blackbird. It is the fastest aircraft propelled by air-breathing engines. The Blackbird’s performance and operational achievements placed it at the pinnacle of aviation technology developments during the Cold War. The airplane was conceived when tensions with communist Eastern Europe reached levels approaching a full-blown crisis in the mid-1950s. U.S. military commanders desperately needed accurate assessments of Soviet worldwide military deployments, particularly near the Iron Curtain. Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’s subsonic U-2 (see NASM collection) reconnaissance aircraft was an able platform but the U. S. Air Force recognized that this relatively slow aircraft was already vulnerable to Soviet interceptors. They also understood that the rapid development of surface-to-air missile systems could put U-2 pilots at grave risk. The danger proved reality when a U-2 was shot down by a surface to air missile over the Soviet Union in 1960.

Lockheed’s first proposal for a new high speed, high altitude, reconnaissance aircraft, to be capable of avoiding interceptors and missiles, centered on a design propelled by liquid hydrogen. This proved to be impracticable because of considerable fuel consumption. Lockheed then reconfigured the design for conventional fuels. This was feasible and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), already flying the Lockheed U-2, issued a production contract for an aircraft designated the A-12. Lockheed’s clandestine ‘Skunk Works’ division (headed by the gifted design engineer Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson) designed the A-12 to cruise at Mach 3.2 and fly well above 18,288 m (60,000 feet). To meet these challenging requirements, Lockheed engineers overcame many daunting technical challenges. Flying more than three times the speed of sound generates 316° C (600° F) temperatures on external aircraft surfaces, which are enough to melt conventional aluminum airframes. The design team chose to make the jet’s external skin of titanium alloy to which shielded the internal aluminum airframe. Two conventional, but very powerful, afterburning turbine engines propelled this remarkable aircraft. These power plants had to operate across a huge speed envelope in flight, from a takeoff speed of 334 kph (207 mph) to more than 3,540 kph (2,200 mph). To prevent supersonic shock waves from moving inside the engine intake causing flameouts, Johnson’s team had to design a complex air intake and bypass system for the engines.

Skunk Works engineers also optimized the A-12 cross-section design to exhibit a low radar profile. Lockheed hoped to achieve this by carefully shaping the airframe to reflect as little transmitted radar energy (radio waves) as possible, and by application of special paint designed to absorb, rather than reflect, those waves. This treatment became one of the first applications of stealth technology, but it never completely met the design goals.

Test pilot Lou Schalk flew the single-seat A-12 on April 24, 1962, after he became airborne accidentally during high-speed taxi trials. The airplane showed great promise but it needed considerable technical refinement before the CIA could fly the first operational sortie on May 31, 1967 – a surveillance flight over North Vietnam. A-12s, flown by CIA pilots, operated as part of the Air Force’s 1129th Special Activities Squadron under the "Oxcart" program. While Lockheed continued to refine the A-12, the U. S. Air Force ordered an interceptor version of the aircraft designated the YF-12A. The Skunk Works, however, proposed a "specific mission" version configured to conduct post-nuclear strike reconnaissance. This system evolved into the USAF’s familiar SR-71.

Lockheed built fifteen A-12s, including a special two-seat trainer version. Two A-12s were modified to carry a special reconnaissance drone, designated D-21. The modified A-12s were redesignated M-21s. These were designed to take off with the D-21 drone, powered by a Marquart ramjet engine mounted on a pylon between the rudders. The M-21 then hauled the drone aloft and launched it at speeds high enough to ignite the drone’s ramjet motor. Lockheed also built three YF-12As but this type never went into production. Two of the YF-12As crashed during testing. Only one survives and is on display at the USAF Museum in Dayton, Ohio. The aft section of one of the "written off" YF-12As which was later used along with an SR-71A static test airframe to manufacture the sole SR-71C trainer. One SR-71 was lent to NASA and designated YF-12C. Including the SR-71C and two SR-71B pilot trainers, Lockheed constructed thirty-two Blackbirds. The first SR-71 flew on December 22, 1964. Because of extreme operational costs, military strategists decided that the more capable USAF SR-71s should replace the CIA’s A-12s. These were retired in 1968 after only one year of operational missions, mostly over southeast Asia. The Air Force’s 1st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (part of the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing) took over the missions, flying the SR-71 beginning in the spring of 1968.

After the Air Force began to operate the SR-71, it acquired the official name Blackbird– for the special black paint that covered the airplane. This paint was formulated to absorb radar signals, to radiate some of the tremendous airframe heat generated by air friction, and to camouflage the aircraft against the dark sky at high altitudes.

Experience gained from the A-12 program convinced the Air Force that flying the SR-71 safely required two crew members, a pilot and a Reconnaissance Systems Officer (RSO). The RSO operated with the wide array of monitoring and defensive systems installed on the airplane. This equipment included a sophisticated Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) system that could jam most acquisition and targeting radar. In addition to an array of advanced, high-resolution cameras, the aircraft could also carry equipment designed to record the strength, frequency, and wavelength of signals emitted by communications and sensor devices such as radar. The SR-71 was designed to fly deep into hostile territory, avoiding interception with its tremendous speed and high altitude. It could operate safely at a maximum speed of Mach 3.3 at an altitude more than sixteen miles, or 25,908 m (85,000 ft), above the earth. The crew had to wear pressure suits similar to those worn by astronauts. These suits were required to protect the crew in the event of sudden cabin pressure loss while at operating altitudes.

To climb and cruise at supersonic speeds, the Blackbird’s Pratt & Whitney J-58 engines were designed to operate continuously in afterburner. While this would appear to dictate high fuel flows, the Blackbird actually achieved its best "gas mileage," in terms of air nautical miles per pound of fuel burned, during the Mach 3+ cruise. A typical Blackbird reconnaissance flight might require several aerial refueling operations from an airborne tanker. Each time the SR-71 refueled, the crew had to descend to the tanker’s altitude, usually about 6,000 m to 9,000 m (20,000 to 30,000 ft), and slow the airplane to subsonic speeds. As velocity decreased, so did frictional heat. This cooling effect caused the aircraft’s skin panels to shrink considerably, and those covering the fuel tanks contracted so much that fuel leaked, forming a distinctive vapor trail as the tanker topped off the Blackbird. As soon as the tanks were filled, the jet’s crew disconnected from the tanker, relit the afterburners, and again climbed to high altitude.

Air Force pilots flew the SR-71 from Kadena AB, Japan, throughout its operational career but other bases hosted Blackbird operations, too. The 9th SRW occasionally deployed from Beale AFB, California, to other locations to carryout operational missions. Cuban missions were flown directly from Beale. The SR-71 did not begin to operate in Europe until 1974, and then only temporarily. In 1982, when the U.S. Air Force based two aircraft at Royal Air Force Base Mildenhall to fly monitoring mission in Eastern Europe.

When the SR-71 became operational, orbiting reconnaissance satellites had already replaced manned aircraft to gather intelligence from sites deep within Soviet territory. Satellites could not cover every geopolitical hotspot so the Blackbird remained a vital tool for global intelligence gathering. On many occasions, pilots and RSOs flying the SR-71 provided information that proved vital in formulating successful U. S. foreign policy. Blackbird crews provided important intelligence about the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and its aftermath, and pre- and post-strike imagery of the 1986 raid conducted by American air forces on Libya. In 1987, Kadena-based SR-71 crews flew a number of missions over the Persian Gulf, revealing Iranian Silkworm missile batteries that threatened commercial shipping and American escort vessels.

As the performance of space-based surveillance systems grew, along with the effectiveness of ground-based air defense networks, the Air Force started to lose enthusiasm for the expensive program and the 9th SRW ceased SR-71 operations in January 1990. Despite protests by military leaders, Congress revived the program in 1995. Continued wrangling over operating budgets, however, soon led to final termination. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration retained two SR-71As and the one SR-71B for high-speed research projects and flew these airplanes until 1999.

On March 6, 1990, the service career of one Lockheed SR-71A Blackbird ended with a record-setting flight. This special airplane bore Air Force serial number 64-17972. Lt. Col. Ed Yeilding and his RSO, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Vida, flew this aircraft from Los Angeles to Washington D.C. in 1 hour, 4 minutes, and 20 seconds, averaging a speed of 3,418 kph (2,124 mph). At the conclusion of the flight, ‘972 landed at Dulles International Airport and taxied into the custody of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. At that time, Lt. Col. Vida had logged 1,392.7 hours of flight time in Blackbirds, more than that of any other crewman.

This particular SR-71 was also flown by Tom Alison, a former National Air and Space Museum’s Chief of Collections Management. Flying with Detachment 1 at Kadena Air Force Base, Okinawa, Alison logged more than a dozen ‘972 operational sorties. The aircraft spent twenty-four years in active Air Force service and accrued a total of 2,801.1 hours of flight time.

Wingspan: 55’7"

Length: 107’5"

Height: 18’6"

Weight: 170,000 Lbs

Reference and Further Reading:

Crickmore, Paul F. Lockheed SR-71: The Secret Missions Exposed. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1996.

Francillon, Rene J. Lockheed Aircraft Since 1913. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Johnson, Clarence L. Kelly: More Than My Share of It All. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.

Miller, Jay. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works. Leicester, U.K.: Midland Counties Publishing Ltd., 1995.

Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird curatorial file, Aeronautics Division, National Air and Space Museum.

DAD, 11-11-01

One of the Seven Sister houses built by Captain Arnold in Mannum in 1911. They are all identical and made of pressed tin.

Image by denisbin

The historic port township of Mannum is located in one of the very scenic regions of the Murray where high cliffs of Tertiary limestone have been exposed by the meandering river. This limestone is laid down over clay layers and the stone was the obvious building material for buildings in Mannum from its origins. The town name came from the local Aboriginal word for place of many ducks. The first white people to see this area were Captain Charles Sturt and his party of explorers who came down the Murray to its mouth in 1830. In 1839 when the government was offering Special Surveys for the huge sum of £4,000 the so called Thirty Nine Sections survey was taken out along the Murray River where Mannum now stands. A consortium of investors took out this Special survey including John Cocks, Osmond Gilles (the Colonial Treasurer), Edward John Eyre (the explorer), and William Leigh (a Staffordshire benefactor of both the Anglican and Catholic churches in SA). Gilles and Leigh held the largest parcels of the 4,000 acres granted with Gilles’ land on the Adelaide side west of the Murray and Leigh’s on the eastern side. Their land covered the areas from Mannum to where Reedy Creek enters the Murray at Caloote. Both were primarily speculators and no real development happened in the area at this time around 1839. The economic activity of the district occurred on the pastoral lease land of John Baker who held most of the land from the Tungkillo area down to Mannum and the Murray from 1843 onwards. A decade (1853) later William Randell of Gumeracha took out pastoral leases on land between Mannum and the Mt Lofty Ranges to the north of Baker’s leases. His run was called Mannum!

Randell’s interest in the Murray and Mannum began back in 1850 when he would have heard that the Governor, Sir Henry Young, his wife, and a party of others cruised up the Murray from Wellington SA to Wentworth in NSW. Governor Young saw the potential of the river for navigation. A committee was established to investigate this and it included William Younghusband, a friend of Captain Cadell of Goolwa, George Fife Angas and John Baker of Tungkillo. The governor offered a reward for the first paddle steamer to venture up the Murray from Goolwa to Wentworth in NSW and Swan Hill in Victoria to prove its navigability. Younghusband worked with Captain Cadell to get this prize money. Cadell named his boat after the wife of the Governor, Lady Augusta. Meantime, without “entering” the race to navigate up to Wentworth, Captain Randell of Mannum readied his paddle steamer to navigate up to Wentworth and beyond. He had taken out his pastoral lease on the Mannum station in 1853. Randell named his boat after his mother, Mary Ann. Randell set out first for Wentworth (and Echuca beyond) but both boats arrived in Wentworth about the same time in August 1853. Because of his connections to Younghusband and the Governor, who had travelled on Cadell’s boat, Captain Cadell received the prize money of £4,000. Because this smacked of favouritism with almost a touch of official corruption the newspapers in Adelaide complained. Randell asked for nothing but was given a “small financial “reward (£300) by the government. The important outcome of the “race” was the beginnings of the River Murray steamer or paddle boat trade.

In turn this river trade led to the establishment of a small settlement at Mannum but it growth was very slow. Randell built a wool store shed on the banks of the Murray at his wharf on his sheep property at Mannum. This was 1854 and the shed was the first structure in what was to become Mannum. Two years later (1856) Randell built a house at Mannum and opened a store here for passing trade. Around that time the government began selling freehold blocks of 50 to 80 acres along the Murray. Consequently the first “settlers” arrived in Mannum, William Baseby and Carl Polack. The first hotel was opened, the Old Bogan, in 1860. The government could see a town emerging privately so they surveyed a government town and port in 1864 downstream from Randell’s wharf area, just beyond what is now the Mary Ann Reserve. Randell had the best spot and the government town did not develop so Randell had a private town surveyed in 1869. This prospered and constitutes the central part of Mannum today. Settlers took up town blocks; Randell donated land for a school in 1871, a flour mill operated by another family opened in 1876, and Mrs. Randell had opened the Bogan store in 1863. More stores followed. The government ferry service began in 1875 and Mannum Council was formed in 1877. Ironically this mid 1870s boom also saw the death of William Randell’s father in Gumeracha. He died at the family estate Kenton Park at Gumeracha in 1876 and is buried in the Baptist church cemetery there. But the town of Mannum was still developing with the churches opening: the Methodist Church in 1880 – replaced 1896; St. Martin’s Lutheran Church in 1882; the Zion Lutheran in 1893; the Presbyterian Church in 1886; the Anglican Church in 1910; and finally the Catholic Church in 1913. The town Institute opened in 1882 and the private school of 1871 was taken over by the state government in 1885. This real boom in the town’s growth came after the settlement of the Murray Flats for wheat farming from 1872 onwards. The founder of Mannum, William Randell died in 1911 but after his father had died in 1876, William Randell had left Mannum and retired to Kenton Park in Gumeracha. His son Murray Randell took over the family river boat business in Mannum from 1899 onwards and had full control of it from 1911. Flour from the family mills in Gumeracha was carted to Mannum and then shipped to the gold mining centres around Bendigo in the 1860s and 1870s. Apart from Mannum, the Randells also had shipping offices in Wentworth.

Among the many stores and businesses in Mannum was the Eudunda Farmers store number 32 which opened in 1926. Like a number of Eudunda Farmers Stores it is still operating in the same location in the Main Street but under the Foodland banner these days.

Industry in Mannum.

1. Walker & Sons Flour Mill. Benjamin Walker had managed a flour mill in Mt Torrens for some time. He moved to Mannum and laid the foundation stone of a new flour mill in 1874 opening it two years later just as the farming boom began on the Murray Flats. It was updated with rollers in 1888 and the steam boiler was replaced with a gas one in 1910. Flour milled here often ended up in Bourke or Wentworth or even parts of southern Queensland near Cunnamulla. It was transported upstream by paddle steamers. When Benjamin died in 1884 his son John took over the mill. Amazingly the mill remained in the Walker family and operated for over 100 years, probably a record for SA. It closed in 1978 after 102 years of operation. Today only four flour mills are left in SA – Cummins, Strathalbyn, Port Adelaide and Mile End compared with 65 at the time of federation in 1901. No SA flour is exported today.

2. Dry Dock. William Randell formed ‘The River Murray Dry Dock Company’ around 1874 to finance the dock which he purchased from Landseer Shipping agents in Milang. The dry dock was floated up to Mannum and located into the river bank so that it was no longer a floating dock. A cutting was made into the bank to accommodate the 144 feet long dry dock. It took over a year to complete the work for the dock to open for business in 1876. With so many steamers plying the river the dry dock was always busy repairing barges and steamers and it created employment for a number of local men but it never made any significant financial returns for William Randell. After William Randell died in 1911 the dry dock was sold to a Swedish resident of Mannum, Johan Arnold, a riverboat man. Arnold had settled in Mannum in 1889. He worked the dry dock and built ships in Mannum including the Renmark, J.G. Arnold, Wilcannia, Nellie, Mundoo, Goldsborough and Murrumbidgee and some other barges. He then established his own shipping company called River Steamers Limited. They traded up to Hay, Wentworth and beyond. He later built the largest steamer ever built in SA, the Mannum. It was 150 feet long. Arnold soon had 80 men on his payroll between the dry dock and his shipping company, spread across all the major river ports where he had shipping offices. Disaster struck in 1921 when the Mannum caught fire whilst docked in Mannum. It was destroyed. Arnold’s house was called Esmeralda. He donated nearby land for the Mannum Hospital and the Anglican Church and he subdivided the rest of his land for town blocks. Captain Arnold died in 1949.

3. Shearers. John and David Shearer arrived in SA from Scotland in 1852. John followed in his father’s footsteps and learnt to be a blacksmith opening his first business in Mt Torrens in 1871 the year he married his 15 year old bride. Five years later in 1876 he opened a blacksmithing works in Mannum. It grew slowly. Brother David had joined the business in 1877 and he helped with the expansion of the business. John invented and patented throughout Australia wrought iron plough shears in 1888 that were a quarter of the price of most others. They were also not brittle like the cast iron plough shears and they lasted longer. The business now expanded greatly with an Australia wide market. They also produced stump jump ploughs and mechanical parts for river steamers. By 1919 Shearers employed over 100 people making agricultural implements, most of which were transported interstate although many of these products were produced in their Kilkenny plant in Adelaide which they had opened in 1904. They made strippers, wagons, harrows, ploughs, harvesters etc. In 1910 the partnership dissolved with David and sons keeping the Mannum plant and and John and sons keeping the Kilkenny plant. At that time David moved the Mannum Shearer factory from Anna Street out to Adelaide Road.

During World War One David’s Mannum plant made ammunition wagons, stirrups etc. In 1952 Shearers became a public company and consequently in 1972 it was taken over by another Adelaide agricultural machinery manufacturer Horwood Bagshaws. They then sold up the Adelaide works and continued production in Mannum. At its peak Horwood Bagshaws employed around 380 people in Mannum. After going into receivership in 1990 the struggling manufacturer was purchased in 1998 by Sweeney Investments from Adelaide. This company still markets implements as Horwood Bagshaws but it also does engineering work for mining companies, defence organisations, and other industries located all over Australia. It employs around 50 people and numerous contractors.

But David Shearer the founder is known for more than being an agricultural implement maker. He was a self educated scientists and “dreamer.” In 1907 he joined the NSW Branch of the British Astronomical Association. He went on to build his own telescope and observatory, the first private one in SA. The simple limestone building, now rendered with cement, had a typical domed roof with sliding panels on a steel track. The telescope is gone and the roof would have to be altered again for the building to be used as an observatory. The adjoining David Shearer House has also been altered especially Shearer’s octagonal lookout tower for night sky observations. Both buildings are on the Register of the National Estate. David Shearer’s other claim to fame is the invention of the first motor car in Australia. In the early 1890s he designed and then built in 1897 a steam powered and propelled vehicle which travelled at 15 miles per hour. He based his design on the transfer of power from engine to wheels that had been used for steam powered tractors. The first car to appear in England was in 1899 and Henry Ford developed his first car in the USA in 1908. David Shearer was ahead of his time but his invention was based on steam power and the future for cars was on the petrol based vehicles invented in Germany in 1885. (Benz began manufacturing petrol driven cars in Germany in 1888 and Bernardi invented the first petrol driven motorcycle in 1882 in Italy.) Shearer’s car however, managed trips of up to 100 kms and he drove it from Mannum to Adelaide in 1900. David then turned his inventing attentions to a mechanical harvester. The Shearer car is now in the Birdwood Mill Museum.

4. Butter factory. The old butter factory which has more recently been an antiques and collectibles shop was established in 1924. It opened as the Producers Supply and Butter Company. It competed with Farmers Union which had opened a butter factory in Murray Bridge in 1922. The Mannum butter factory was located by the river as most milk arrived at the factory by milk barge. (Farmers’ Union in Murray Bridge owned four river barges for carting fresh milk to its factory there). Archie Schofield purchased the Mannum butter factory and took control in 1932. After a fire it was rebuilt in 1935. The Schofields operated the butter factory until it was sold to Farmers’ Union in 1955. It was then submerged by the 1956 Murray flood and appears not to have re-opened as a butter factory.

Paddle Steamer Marion and Mannum Dock Museum.

The Museum entrance fee is .50 or for a concession. It includes the Randell Dry Dock, the Paddle Steamer Marion, the Keys Beam engine and displays on Murray River floods, the life cycle of the Murray, the Ngarrindjeri dreaming, and the history of white settlement in Mannum. But from the outside you can still see the restored Paddle Steamer Marion provided it is not cruising the Murray. Its history goes back to 1897 when it was built by Landseers at Milang. At over 100 feet long it was one of the bigger river steamers. After a long history of river trading her transportation days ended when her owners went into liquidation in 1952. She was sold on to several owners before she ended up being a floating boarding house. In 1963 the National Trust purchased her as a monument to the riverboat trade. She was sailed down to Mannum to be the centre piece of the NT Museum there. For over thirty years she languished in a dilapidated state in the Museum. In 1989 she was restored so that she could be used as a working river vessel with her being recommissioned in 1994. She occasionally does river trips for paying passengers. Some of her most interesting journeys were promotional trips paid for by the SA government. One was in 1910 for the Scottish Agricultural Commission when members visited SA. They travelled down from Mildura in the PS Marion. Another was in 1915 when the SA government paid for a trip by Australian parliamentarians, both Federal and state parliamentarians. Politicians from all states except Western Australian participated including the Premier of NSW, the Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, and the Attorney General, Billy Hughes who became the next Prime Minster. The promotional journey was to familiarise the politicians with the construction of Weir Number One across the Murray at Blanchetown which was then nearing completion.

Some Mannum Buildings.

1. The Anglican Church of St. Andrew was opened in 1910. Before that time the Anglicans attended services when the paddle steamer Etona visited the town.

2. The Mannum hospital was built in 1921 on land donated by Captain Arnold. The grounds incorporated his former home, Esmeralda which he purchased in 1905. Captain Arnold had settled in Mannum in 1889.

3. The Baptist Church. It began life as the Presbyterian Church in 1886 but was sold just three years later to the Baptists. The Randell family were Baptists and worshipped there.

4. Shearer Business Complex dating from 1876. The site of the original Shearer factory is now a car park but with fine memorial gates. Along one side is a fine old stone building which was once the Shearer company offices but it is now a Laundromat. Above the factory site is the Shearer House which is actually in Anna Street. A fine set of steps leads up from the Main Street to Anna Street. It is an imposing house overlooking the Main Street with a central part and two added wings. Originally one wing had a tower for astronomical observations. Adjacent to the house is the ruins of the Shearer Observatory. It is a round structure and once had a domed roof with sliding panels for the telescope to be used for observation. It is on the Register of the National Estate but urgently needs restoration.

5. The Institute was opened in 1882 and extended in 1911 with a Classical style façade with a triangular pediment above the entrance.

6. The Pretoria Hotel in the Main Street. It opened in 1900 when the Boer War was at its height hence the name.

7. The Mannum Hotel. The first hotel was erected on this site in 1866 for Randell. It was rebuilt as the Bogan Hotel in 1869. The upper floor was added in the 1870s. It was also the site for the first Council meetings of Mannum.

8. The Old Woolshed was built by Captain Randell in 1854 as the first structure in his Port of Mannum.

9. St. Martin’s Lutheran Church opened in 1882. A Lutheran school operated here from 1884-1917 when the Government closed all Lutheran schools. For many years (43) the congregation as led by Pastor Ey. A second congregation opened a second Lutheran church in Mannum called the Zion Lutheran in 1893. Its parent church was in Palmer.

10. Bleak House. The four roomed house built by Captain Randell in 1856 is up the hill from his wharf. It was the first stone structure in the town. This structure would be the rear part of the current building. The front part dates from the 1860s, probably 1869 when Randell subdivided part of his land to create the township of Mannum.

11. The Catholic Church of Mount Carmel. This was opened in 1913.

12. The Methodist Church, now the Uniting. The first church was built in 1880. But the construction was poor and the church was pulled down a few years later. In 1896 the second Methodist church opened on the same site. The current church was built in 1954 and replaced the earlier one.